An Explanation for Immigration, Trade

and the Dissemination of Political and Religious Ideology

along the Silk Roads to Korea

by James C. Schopf

Professor of Political Science

Head of Planning at Academia Via Serica

The Silk Roads were a network of ancient trade routes that stretched over 6,000 miles, by land and by sea from Syria in the West to Korea and Japan in the East and from Siberia in the North to India in the South. The movement from the Silk Road into Korea of people, goods, and ideas related to religion, politics and societal organization has fluctuated throughout history, from periods of heavy exchange to eras of isolation. Puzzling, though, is that the inflow of new political and religious ideologies to Korea did not always coincide with the exchange of people and goods. The period with the freest movement of goods and people from the Silk Road to Korea, during the Mongol domination of the Goryeo Dynasty, did not lead to the conversion of most Koreans to new religions such as Islam or Manichaeism or to the introduction of new ideologies to legitimate political rule. It was in eras of intense interstate conflict and competition, instead, in the proto-Three Kingdoms (108 BCE- 57 BCE) and Three Kingdoms periods in Korea (57 BCE-668 AD), in which new political/religious ideologies to justify rule by a Shaman-King or by a Buddhist Chakravartin-King, swept into the Korean peninsula.

Two different factors account for Korea’s adaptation of foreign political/religious ideologies and openness to imports of foreign goods and the immigration of foreigners in the pre-industrial era. Domination of trade connections to the Korean peninsula by a free trading power opened the peninsula to an inflow of goods and people. Prior to ascendancy of maritime trade this had meant control of critical Northern Chinese Silk Road connection by free trading nomadic pastoral tribes and states, rather than sedentary agricultural civilizations. Heightened interstate competition and conflict, on the other hand, in Northern China, but especially within the Korean peninsula, accounted for the degree to which political/religious ideologies affected Korea.

Control of the Northern China Silk Road entrance to Korea by tribes and states with nomadic pastoral influence allowed goods and people to reach Korea from the West prior to the Han Dynasty, and during the Sixteen Kingdoms and Sui/Tang and Yuan Dynasties. Civilizations controlled by protectionist sedentary agricultural interests, however, such as the Ming were able to dominate land and maritime Silk Roads and close off trade between the West and Korea. Important foreign political, societal, and religious ideas exerted the most impact on Korea, on the other hand, during periods in which warring states and tribes competed for control of the Korean peninsula and the Silk Road region, such as the proto-Three Kingdoms and Three Kingdoms period coinciding with the Han Dynasty and Sixteen Kingdoms period. Foreign religions and political ideologies failed to penetrate China and Korea during periods of stability and unity, such as during the Silla, Goryeo, Joseon, Tang, and Ming and Qing Dynasties.

Theory

The control of nomadic pastoral herding tribes over the Silk Road region in the pre-maritime trade era influenced the movement of goods and people, whereas the level of interstate competition in Korea and in the Silk Road region affected the flow and adaptation of political and religious ideologies within Korea.

Trade in goods moved mostly freely on the continental Silk Road when the region was under the control of pastoral nomadic tribes, or states with pastoral nomadic legacies and influence. Pastoral nomadic groups relied on animals for their survival and moved their habitat several times a year in search of water and grass for their herds. The constant migrations of nomads prevented them from transporting reserves of food or other necessities. This inability to accumulate surplus prevented nomadic groups from tiding themselves over during bad times, or paying specialists, such as artisans, to develop civilization and produce technological goods. Nomadic pastoralists, therefore depended on the trade of meat and animal products in return for grain, clothes and the specialized goods produced by sedentary agricultural societies.

1 Some archeologists controversially claim that nomads were also the architects of the first long-distance trade networks, since travel over hundreds of kilometers in search of grazing land would have familiarized them with long distance trade routes. In any case, though, nomadic pastoralists, unlike agricultural societies, do not have the option of self-sufficiency, and thus more strongly favor free trade policies. Thus trade flowed more freely along the overland Silk Roads to Korea during periods in which the nomadic pastoralist tribes of Central Asia, such as the Northern Wei’s Xianbei Tuoba and the Mongol Yuan Dynasty, or states ruled by families with strong pastoral nomadic roots, such as the Sui and the Tang Dynasties dominated the region of Northern China connecting the Silk Road to the Korean Peninsula.

As the blossoming of the Hundred Schools of Thought philosophical revolution during China’s Warring States period makes evident, an international environment inhabited by states fiercely competing for survival provides fertile grounds for the creation and dissemination of innovative religious, political, and societal ideologies. Effective rule requires popular acceptance of the leader’s exercise of authority. The basis by which rule is justified and legitimated varies by ideology.

2 Leaders facing heightened security threat have an immediate incentive to adopt and implement new governing ideologies that can be effectively utilized to mobilize citizens and extract resources from the population to increase military capabilities. Thus, new ruling philosophies and politically advantageous religions can be expected to more rapidly spread in conditions of heightened inter-state conflict and security threat. The rulers of stable, peaceful kingdoms, on the other hand, are able to rely on long established ideologies, religions and philosophies to justify their rule. Innovative and radical philosophers and religious thinkers are therefore more likely to be suppressed and face banishment under conditions of unified, stable rule. Thus, periods of interstate and intertribal conflict along the Silk Road in Northern China and within the Korean peninsula can be expected to coincide with the most rapid and far reaching spread of governing philosophies and religious ideas. Periods in which China and Korea were united and peaceful should instead coincide with very limited introduction of new political, religious and societal ideologies.

Table 1: The Effect of Interstate Competition and Nomadic Domination of the Silk Road on the Flow of Good and Ideas

| |

Interstate Conflict in Northern China and Korea |

Unified Stable, Rule in Northern China and Korea |

| Nomad control of Northern China Silk Road |

Much exchange of goods and people and of religious, political and societal ideas |

Exchange of goods and people but not much exchange of religious, political and societal ideas |

| Farmer control of Northern China Silk Road |

Little exchange of goods and people but exchange of religious, political and societal ideas |

Little exchange of ideas, goods or people |

Han Dynasty China/ Proto-Three Kingdoms Korea

While the historical record during this period is fragmentary, the period of the Han Dynasty and the proto-Three Kingdoms period (108BCE - 57BCE) was characterized by warfare between numerous small tribal states on the Korean peninsula, including Goguryeo, Dongye, Baekje, Mahan, Ye, Jinhan and Byeonhan and domination of the Silk Road region bordering Korea by nomadic pastoral tribes.

Although the exact origins of Korean Shamanism remain unknown, scholars point to a North and Central Asian origin five thousand years ago. Even during the Han Dynasty’s expansion into the Korean peninsula in 108 BCE, Korea bordered proto-Turk and proto-Mongol pastoral nomadic tribes to the North, including Xianbei, Xiongnu, Wuhuan, Dingling, Buyeo, Yilou and others.

The nomadic tribes sought control of strategic resources, such as watering places and good pasturage for their yaks, sheep, or horses, and often raided their weaker neighbors. In the hostile steppe environment, where a tough reputation was one’s best defense, disputes were likely to produce violent vendettas and feuds lasting generations. In such an environment of constant tribal warfare

3, tribal chiefs placed a premium on ideologies which would enable them to legitimate and expand their authority over the tribe. It was in this environment in which Korean tribes, including the royal families of Goguryeo, Baekje and Silla adopted the concept of the Shaman King to expand their political power.

Items excavated from royal Silla tombs in the capital of Kyungju reveal that during the proto-three kingdoms period, the politico/religious model of the Shamanistic priest King reached Korea on the Silk Roads from Siberia and Northern Asia. Shamanism is based on the idea of a layered universe, in which a shaman derives supernatural powers from travel between the physical human world and the unseen spiritual world. A Shaman Chief thus possesses near god-like status among their people, from which they derive ownership rights over valuable economic assets and the political authority to determine rules for their tribe. The Shaman Chief’s key duty is to make things right with the spirits, who are believed to be the cause of all troubles and calamities, including war, drought, flood or sickness. The Shaman Chief can thus demand sacrifice of the people to placate the spiritual powers, increasing their power over the spiritual world and strengthening their rule over subjects.

4

Fig. 1) Silla Dynasty Crown, found in Tomb #98; Gyeongju National Museum, ©2008 Daniel C. Waugh |

In the case of the Silla Dynasty, a shamanistic foundation myth claimed that the progenitors of the dynasty’s three ruling royal families (the Pak, Kim and Seok clans) had been born from eggs, providing their descendants with a unique link to the spiritual world and nature powers. Silla’s Kings carried the title ‘Chachaung’ meaning shaman or priest. |

The North Asian Silk Road influence evident in the golden crowns and belts found in the royal tombs of the Silla’s capital in Kyungju, indicates that Silla Kings fulfilled a dual political/religious role as a king/shaman-priest. Archeologists excavated several 5th century CE golden crowns, each with a stylized tree rising in front of the headband and a representation of antlers on each side. The crowns were studded with what appeared to be thin gold-sheet “leaves” and comma-shaped jade pendants (Fig. 1).

5

The tree of life symbol, golden leaves, antlers and comma-shaped pendants found on Silla crowns have been linked to Shamanism in earlier Central Asian Bactrian crowns, Xiongnu burials, Xianbei golden deer heads, and Scythian deer masks. Yi Songnan

6 argues that the technique and style of the Silla crown show a Bactrian origin and heavy Greek influence which spread via trade through the Xianbei, Xiongnu, and Goguryeo to Silla, which Pierre Cambon

7 also points out, bypassed China. Like the Silla crowns, the fourth century CE Central Asian Bactrian crowns unearthed at Tillya Tepe in Afghanistan had also been constructed by adding an ‘upright tree of life’ that was studded with round, thin golden leaves attached by thin gold thread.

8 The leaves, tree and birds were ritual symbols connected to shamanism (Fig. 2).

9

| The Silla crown’s comma-shaped pendants (Gogok 곡옥) were another Shamanism linked symbol, but with roots in Northern Asia. The comma shape which functioned as a totem symbol, and has been hypothesized as representing a bear or tiger claw, was well-known in Xiongnu burials at Noyon uul in Mongolia and Scythian tombs at Pazyryk in Siberia back to the 5th century BCE (Fig. 3).10

|

Fig. 2) Royal crown from Tillia tepe; Musee Guimet |

Fig. 3) Comma-shaped Pendants, Gyeongju National Museum |

Fig. 4) Xianbei Golden Deer Head, Canadian Museum of Civilization |

The Silla crown’s antlers had been influenced by fifth century CE Xianbei golden deer heads with antlers decorated with ‘Silla-style’ golden leaves found in present day inner Mongolia (Fig. 4).11 |

| 12Staffan Rosén hypothesizes a further antler connection in the form of Shamanistic Scythian ‘deer–masks,’ excavated at Pazyryk ca. 5th–3rd centuries BCE, which had been used to turn horses into a religiously more important deer (Fig. 5). |

Fig. 5) Scythian Deer Mask, The State Hermitage Museum |

Fig. 6) Golden Belt with Pendants from Kumgwanchong Tomb in Gyeongju |

The Silla also modeled their royal golden belts on those of Central Asian nomads, which provided mounted warrior quick access to a variety of instruments attached by perpendicularly hanging leather strips to a girdle. The Silla transformed Central Asian work belts to serve in Shamanistic ceremonies meant to uphold the status of the royal family, hanging from a golden girdle functionally symbolic pendants made of pure gold and jade which were miniatures of the objects (knife, tweezers, fish) they represented (Fig. 6). |

Nomadic Northern Siberian Scythians also played a significant role carrying Middle Eastern first millennium BCE iron forging technology into eastern Siberia by 700 BCE and on to the Korean peninsula by 400 BCE. The Scythians were leaders in iron dagger manufacturing, and bronze daggers in the Scythian shape were found in Daegu on the Korean peninsula.

13

Early first century CE tiger and horse-shaped bronze belt buckles from Yongchon Korea also reflected the Scythian model. The burial of Silla kings with horses and horse trappings was another sign of early Siberian and shamanistic influence.

Sixteen Kingdoms China/ Three Kingdoms Korea

Following the fall of the Han Dynasty, the region of Northern China adjacent to Korea containing the Silk Road came under the control of nomadic pastoral peoples, who engaged in prolonged warfare. Interstate conflict between the three kingdoms in Korea and among the warring nomadic tribes of Northern China who dominated Korean access to the Silk Road played an important part in facilitating the introduction of Buddhism to Korea, which subsequently expedited the consolidation of the Sui’s unification of China and Silla’s unification of the Korean peninsula. The nomad-ruled kingdoms of Northern China welcomed foreign merchants, particularly Persians, Sogdians, and Turks, and goods flowed freely along the open Silk Road to the Korean peninsula, as indicated by the large number of glass vessels, daggers, and indigenous archaeological materials, such as rhytons, unearthed in Silla tombs during this period.

After the fall of the Han Dynasty, China entered a period of division for several hundred years. While Han Chinese ruled unified kingdoms in southern China, from 304 to 439 CE the Silk Road region in Northern China was home to the ‘Sixteen Kingdoms of the Five Barbarians’ a series of short-lived dynastic states founded by five nomadic pastoral peoples, the Xiongnu, Xianbei, Di, Jie, and the Tibetans, who engaged in continuous warfare with one another. While Buddhism received a hostile reception under the Qin Dynasty

14 and was conflated with Daoism under the Han Dynasty, the warring tribal chiefs of the north viewed Buddhism as a critical means through which to mobilize and motivate their people to gain an advantage against rivals. In multi-ethnic Northern China, tribal chiefs could gain legitimacy, prestige, loyalty from Buddhists of any tribe by identifying as a Chakravartin King, like the famous Mauryan Emperor Ashoka (268-239 BCE), a compassionate and enlightened Buddhist ruler who practiced tolerance, preserved social harmony, supported the Buddhist monastic order and governed to spread the Buddha’s universal truths and help commoners progress towards nirvana. While Shamanism was well equipped for strengthening internal tribal loyalty, it was poorly suited for gaining allegiance from rival tribe members, who believed in the supernatural ability of their own tribal chiefs.

After Buddhism’s spread into Northern China in the 3rd century the nomadic Xianbei Tuoba rulers of the Northern Wei Dynasty (386-534 CE) utilized Buddhism to unify control over Northern China. The early emperors of the Northern Wei gained legitimacy and support from Central Asian nomadic and Chinese Buddhist followers by claiming to be the reincarnated Buddha, while their later emperors supported the spread of Buddhism in accordance with the Chakravartin King model. The founder of the Sui Dynasty (581-618 CE) Yang Jian, a.k.a. Emperor Wen, the first ruler to reunify China, and Tang Taizong, the founder of the Tang Dynasty (618-907 CE), both also legitimated their positions by generously contributing to Buddhist monasteries and presenting themselves as Buddhist Chakravartin kings.

On the Korean peninsula during the Three Kingdoms Period, a direct connection to the Silk Road through the nomadic Tuoba tribe-ruled Northern Wei and conditions of fierce interstate warfare and competition provided the royal families of Silla, Goguryeo and Baekje with a clear incentive to broaden their appeal by adopting state Buddhism and the Chakravartin King model. In contrast, entrenched ruling elites in stable, unified and peaceful southern China resisted Buddhism in favor of Confucian and Daoism. Goguryeo (372) and Baekje (384), therefore adopted Buddhism nearly one hundred years before Emperor Wu of the Liang Dynasty in southern China decided to provide official support to Buddhism.

15

Despite Silla’s initial resistance to Buddhism until 527 CE, the Chakravartin Buddhist King model facilitated Silla’s unification of the Korean peninsula by offering Silla rulers a means through which to transcend tribal barriers and gain legitimacy from Buddhist followers in the conquered states of Baekje and Goguryeo. The royal families of Baekje and Goguryeo had also legitimated their rule through Shamanism, claiming superhuman powers and unique connections to the heavens. Following centuries of indoctrination in their own royal family’s supernatural ability, the former subjects of these conquered states would have resisted transferring loyalty to the rulers of an enemy tribe, Silla, long perceived as inferior. The universal appeal of Buddhism and the Chakravartin king model, though, enabled Silla royal family to gain legitimacy from the subjects of conquered Baekje and Gogeoryo subjects. Buddhist politico-religious ideology also served the cause of building a powerful centralized state with a sacred royal authority, helping Silla to emerge as a strong political power in the peninsula in the sixth and seventh centuries King Jinheung (540-576) strengthened Silla state power by supporting Buddhism and constructing numerous monasteries. By welcoming foreign monks and appointing the eminent Goguryeon monk, Hyeryang as Silla’s Chief Monk, or sungtong, Jinheung signaled that Buddhism trumped tribe as a legitimating ideology. Jinheung legalized monastic orders, and became a monk himself, unifying Buddhism with the state. He organized the Hwarang youth warriors, who were believed to be the incarnation of Maitreya Bodhisattva, identified as a Chakravartin King, and like the famous Mauryan Emperor Ashoka, erected Buddhist monuments throughout the land, viewing territorial expansion as a conquest of truth. The Silla kings and queens immediately succeeding Jinheung maintained the policy of Buddhist political mobilization and religious patriotism, sanctifying the royal house by adopting Buddhist names. Under the slogan of “Hoguk Bulgyo’ or ‘Nation defending Buddhism,’ the Buddha and his teachings underpinned the power and legitimacy of the king, and were in turn protected by him.

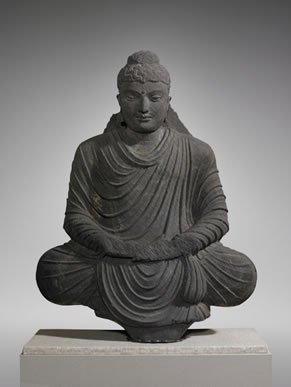

Fig. 7) Gandhara Seated Buddha, 3rd century CE, dark gray schist, Yale Art Museum |

Unlike Shamanism, Buddhism required construction of specially designated buildings for rituals and ceremonies, such as temples, monasteries, nunneries, libraries and schools, leading to introduction of Indian, Hellenistic and Persian artistic and architectural influences along the Silk Road. Greek craftsmen in Gandhara, which had previously been part of Alexander the Great’s Empire, introduced the practice of sculpting Buddha and Bodhisattvas based on their earlier portrayal of Zeus and Hercules. Buddhas were sculpted with Hellenistic artistic influences, such as the realistic depiction of drapery, while the eyes, elongated ear lobes, and oval-shaped face derived from Indian iconography (Fig. 7). Buddhist monks brought Gandharan sculptures of the Buddha to Silla, greatly influencing Silla’s Buddhist art. |

The practice of carving the image of Buddha in stone and stupas in cliff walls and natural caves also spread from Gandhara to Korea. Silla craftsmen carved stone images on the cliff sides of sacred mountains, such as Mt. Namsan in Kyungju and created Seokguram, an artificial granite grotto on Mt. Tohamsan for exclusive use by the Silla royalty.

The Seokguram Buddha was likely modeled after a Buddha at the Mahabodhi Temple at Bodhgaya, the site of Shakyamuni’s enlightenment in northeastern India (Fig. 8).16 |

Fig. 8) Seated Buddha at Seokguram Grotto, near Gyeongju

|

The builders of Silla’s Bulguksa Temple ‘Buddha Nation Temple’ (751 CE) and its stupas were inspired by Indian designs and borrowed ideas from Chinese Buddhist temples (Fig. 9).

Fig. 9) Bulguksa Temple, near Gyeongju |

|

Glass vessels, daggers, and indigenous archaeological materials, such as rhytons, unearthed in Silla tombs during this period also indicated a dynamic flow of goods and the spread of artistic ideas related to design and fashion from the Middle East and Western Asia along the Silk Roads. |

| Since large glass objects were not manufactured in Silla during the Three Kingdom Period, all glass grave goods, including cups, bowls and ewers, had to have been imported. Cut glassware originated in the Persian Sasanian Empire, spread to Xinjiang, to Pingcheng the capital city of the Northern Wei Dynasty (in modern Shanxi Province), and were found in some quantity in Silla tombs (Fig. 10). The earliest glass found in Korea dates |

|

Fig. 10) Glass Vessels from Silla Tombs, Gyeongju National Museum |

from the 2nd century BCE. Glass beads were then regarded as more precious than gold or silver. Glass beads in different colors and shapes as material for necklaces and bracelets were commonly placed in tombs and some may have been locally manufactured.

A Persian–style ceremonial jade-inlaid gold dagger and scabbard excavated from near the tomb of King Michu (262-284) was made with a technique common in Egypt, Greece and Rome and it was likely imported from the West via the Silk Road (Fig. 11). This type of scabbard was found in tombs of the Hun Empire (434–454) from the end of the 4th to the 7th centuries in Siberia and Central Asia.

17

Fig. 11) Golden scabbard in King Michu’s tomb, Gyeongju National Museum |

In contrast to the direct import of glass vessels and daggers, drinking horns, known as rhytons, provided evidence of the transport of ideas related to design technique. Rhytons were drinking containers made out of numerous materials from gold to clay and always contained the head of an animal head (often lions, ibex, rams, or horses) at their lower tip. Rhyton pottery was common in Persian and Greek culture from second millennium BCE and they were copied by Silla craftsmen during the 5th and 6th centuries CE (Fig. 12).

18

Fig.12) Earthenware Rhyton Horse Heads Cups, Silla Three Kingdoms Period (5th century), Bokcheon-dong tombs, Dong-A University Museum |

Other Western items excavated from Silla tombs include a silver bowl engraved with an image resembling the Persian goddess Anahita, gold-plated shoe soles, popular in the Sassanian Kingdom, and golden earrings, caps, shoes, belt buckles, and plaques which were probably a Middle Eastern practice that spread to Goguryeo, Baekje and Silla. |

| During the Three Kingdoms period western and northern Silk Road influences were just as evident in the Goguryeo and Baekje kingdoms. Goguryeo constructed underground tombs with a cornice in the dentil Greco-Syrian style. This technique had originated in Palmyra, spread to Roman-Syrian tombs in the Black Sea region, onward to Bamiyan tombs in Afghanistan and Kizil in Eastern Turkestan and finally to Dunhuang, under Northern Wei control before introduction to Goguryeo. |

Fig. 13) Depiction of the ‘Parthian Shot’ (upper horseman) in Muyong Tomb, Goguryeo 5th century CE, Ji'an city, Jilin province, China |

Kwon Young-pil showed too, how the artistic intellectual concepts, such as the ‘Parthian shot,’ spread to Goguryeo from the West (Fig. 13).

19 The ‘Parthian shot’ was a motif used in painting and sculpture. depicting a military tactic originating in the Parthian kingdom, in which a mounted warrior riding at full gallop turns backwards and with both hands, shoots his bow towards his pursuers. The Scythians, Huns, Turks and Mongols mastered this technique and The Parthian Shot was featured in Goguryeon tomb murals.

Fig. 14) Stone Guardian of King Muryeong’s Tomb, National Treasure #162, 500 CE, Baekje Dynasty, Gongju |

Baekje Kingdom crowns displayed the same tree Shamanistic motif and an animal statue guarding King Muryeong’s tomb (501–523) had been constructed with a Scythian stylized animal horn on a small scale that did not match the rest of the animal’s body (Fig. 14). |

Sui and Tang Dynasty China/ Unified Silla Dynasty Korea

The Sui Dynasty unified Northern and Southern China in 581 CE, and was succeeded by the Tang Dynasty (618-907), which largely inherited its foundation. The Sui and Tang royal families had nomadic roots and maintained trade along the Silk Road, providing Korea access to goods from the West. While the Sui and Tang unified rule of China, Later Silla (661-935 CE) exerted authority over all Korea. Unified, stable rule reduced the need for new political and religious ideologies to broaden legitimacy or extract more resources from the population. So, while this period was characterized by the movement of people and goods on the Silk Road into Silla, the political classes in Silla did not adopt or promote new political/religious ideologies from the Silk Road.

| The Sui and Tang Dynasty royals and elite were of mixed ethnic background with nomadic Xianbei heritage. The founder of the Sui Dynasty, Yang Jian, married into a Xianbei family and had a Xianbei name – Puliuru Jian, while the Tang Emperors had a matrilineal Xianbei origin and preserved many Xianbei customs. Thus the Tang Dynasty, particularly during its first half, remained open to Silk Road influences from the rest of Asia, maintaining the traditional nomadic welcome of foreign merchants, products, art, songs, dances, musical instruments and fashions, as foreign traders from around the world resided in Chinese cities and were depicted in the famous Tang Dynasty tri-color sculptures (Fig. 15).20 Tang ports welcomed ships on the maritime Silk Road from the Middle East, India, Korea, Japan and Southeast Asia. |

Fig. 15) Camel with Musicians, Tang dynasty 723 CE, Tomb of Xianyu Tinghui, Xi’an, National Museum of China, Beijing |

Many Central Asian and Middle Eastern traders and immigrants traveled on the Tang-maintained Silk Road to Silla. Silla traded silk, swords and musk with the Arab world in return for spices and glass items. Hee Soo Lee documents eighteen Muslim scholarly depictions of the lives of Arabs in Silla, Silla’s topography, natural environment and the lives of its people during the Unified Silla era.

21 The official chronicle of the Three Kingdoms era, Samguk Sagi—compiled in 1145—contains further descriptions of commercial items sold by Middle Eastern merchants and widely used in Silla. Evidence of the presence of Central Asian officials in Silla also includes the nine- foot stone guard statues at Silla King Wonsong’s (785-798 CE) tomb, which resemble Uighurs with square jaws, protruding noses, full beards, Central Asian clothing and caps, and deep-set set eyes.

Silla exerted influence abroad through the maritime and land Silk Roads as well. Silla General Jang Bogo (787-841) and his private army and navy of 10,000 headquartered at the Cheongjaejin Garrison on Wando Island patrolled maritime trade routes between East China, Korea and Japan allowing private Sillan traders to dominate East Asian trade networks. Thousands of Sillan merchants set up communities in coastal Shandong and Jiangsu provinces in China, and Silla monks and scholars traveled to Tang China, with some passing the civil service exam and serving in the Imperial guard. Many Sillan monks, including the famous Hyech’o, took pilgrimages to India and back via China and Central Asia. The Japanese Buddhist monk Ennin’s diary gives the impression that Koreans were among the most numerous foreigners in Tang.

Fig. 16) Afrasiab Palace, “The Ambassador’s Painting,” 7th century CE, Samarkand, Uzbekistan |

Traces of Korea can also be found on a section of a wall mural at the Afrasiab palace near modern Samarkand (mid-7th century CE) which depicts two Koreans with round-pommel swords common on the peninsula, wearing clothing depicted on Koguryô tomb murals (Fig. 16). |

Yuan Dynasty China/ Goryeo Dynasty Korea

After the fall of the Tang and division of China into the Liao and Jin in the North and the Song in the South, Genghis Khan united the nomadic tribes of North East Asia, founded the Mongol Empire and launched invasions conquering most of Eurasia from Hungary to Korea. His grandson Kublai Khan established the Yuan Dynasty, with control over Mongolia and China and set about attacking Korea’s Goryeo Dynasty. After six invasions over a thirty-year resistance, Goryeo agreed to become a marriage alliance vassal state of the Yuan dynasty. Korean kings made lengthy stays at the Mongol Yuan court and their Mongol wives exerted great influence over Goryeo politics, selecting officials for posts within the Goryeo government. Mongolian resident commissioners sent to the Goryeo court received provisions and actively participated in Goryeo court affairs.

While Yuan dominance of Goryeo promoted the free movement of people, goods, scientific knowledge and technology, the Yuan’s stable unified rule over China and Korea removed any incentive to embrace a potentially destabilizing or radical new religious ideology as a means of mobilizing the population to increase power. Instead, the Mongols attempted to neutralize the destabilizing political effects of religion by exempting religious leaders from taxation and allowing free practice of religion throughout their multi-faith realm.

As pastoral nomads, the Mongols had long relied on trade with sedentary farmers for necessities like weapons, pottery, grain and clothes. Expansion of the empire increased demands for imports, military supplies, and skilled, literate immigrants who could administrate the new territories. To facilitate trade during the Mongol Empire the Khans established a trade promotion system to meet the merchant’s financial and security needs.

The Mongols offered merchants use of their Yam system of relay stations along the Silk Roads which provided food, shelter and spare horses, set up protective merchant associations called Ortogh, provided tax exemptions, and issued merchants passports allowing safe travel along the Silk Road. Merchants received higher social status than under the Chinese and Persians, and were provided sufficient supplies of paper currency backed with silk and precious metals and even low interest loans.

The system produced an increase of international trade on a level never seen before. Valuable spices, gems, tea, lacquerware, ceramics, and silk headed from East Asia to the Middle East and Europe, while gold, medical manuscripts, astronomical tomes and porcelain moved from the Islamic world east to Asia.

New products, customs, scientific knowledge and foreign immigrants entered the Goryeo Dynasty. Even though the Mongols promoted freedom of religion, and Islamic traders set up communities and mosques within Korea, the stable, united rule in Goryeo restricted demand for new religious and political ideologies. Islam, Manicheanism and Nestorianism did not make lasting inroads into Korean society.

Fig. 17) Goryeo Dynasty Celadon, The Metropolitan Museum of Art |

Korean-Arab exchange rapidly developed after Mongol domination of Goryeo as a vassal from 1270 to 1356. Korean and Middle Eastern sources describe how Central Asians and Middle Easterners permanently settled throughout Korea, taking up positions as Goryeo court officials or as private traders.22 The Goryeo Dynasty’s pale jade colored green ceramics, known as celadon, became a very popular trade item (Fig. 17).22 |

Goryeo became widely known as “Coree” in the Arab world and Europe, providing the nation with its modern name. Members of Central Asian communities assimilated into Korean society while preserving their cultural customs, traditions, and religious rituals, owning and operating shops selling middle eastern products and constructing mosques, known in Korean as Yegungs, including a grand mosque in the Goryeo capital. Lee reports that some Muslim leaders of high social standing were invited to the royal court to recite Qur’anic verses wishing the Korean king a long and prosperous life.

24

From this exchange Goryeo gained sophisticated Islamic knowledge and technology related to astronomy, medicine, calendar science, architecture, music and weaponry. The new Korean lunar calendar was completely based on Islamic astronomical theory and advanced Islamic science contributed to invention of advanced astronomical and meteorological scientific instruments, including the celestial globe, the water clock, the sundial, the astronomical clock and the rain gauge. Koreans were also introduced to new weapons such as catapults, scaling ladders, and siege towers.

Fig. 18) Goryeo Dynasty Drinking Vessel, Wide Brimmed Flask, Hoam Museum |

Arab medical herbs and formulas were introduced to Korea while Arabs in Korea and China brought knowledge of metal movable type printing back to the Middle East.25 Middle Easterners in Goryeo introduced new products like the distilled alcoholic beverage soju, then known as ‘aragi,’ which resulted in the introduction by Goryeo artisans and craftsmen of a tremendous range of forms and decorations on drinking vessels (Fig. 18).26 |

| The Korean elite aristocratic class also took up Mongol customs, such as hunting, and Mongol fashions, such as the plaited Mongolian pigtail and tunics which were portrayed on famous paintings (Fig. 19).27 |

Fig. 19) Suryeopdo, Asan City, S. Korea, ⓒOnyang Folk Museum |

Ming Dynasty China/ Joseon Dynasty Korea

The fall of the Yuan and rise of the protectionist Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) and its control over the Silk Road and influence in Korea led to a sharp decline in the movement of foreign people, goods and political and societal ideologies into Korea. The founder of the Ming Dynasty Zhu Yuanzhang, led a peasant revolt that seized control of China from the Mongols. The Han Chinese ruling family lacked the nomadic favor for merchants, and instead sought to purify China of barbarian influence and create a society of self-sufficient rural communities. Ming Emperors subsequently enacted restrictive policies towards international trade. Political unity in China under Ming rule and in Korea under the Joseon Dynasty (1392–1910) reduced demand for new political or religious ideologies to legitimate rule. The Ming and Joseon instead adopted neo-Confucian ruling ideologies which further marginalized the merchant class.

While the Ming had initially promoted international exchange by sponsoring the seven voyages of Admiral Zheng He and his 317 ship ‘treasure fleet’ (with up to 1,500 sailors on one boat) to Southeast Asia, South Asia, the Middle East and Africa, powerful factions of officials within the civil service, alarmed at the rise of a newly wealthy merchant class, convinced the Emperor to ban oceangoing voyages in 1430.

28 The Ming destroyed records of Zheng He’s voyages in 1470 and by 1525 the treasure fleet had all been burned or rotted away.

In the 1400s Joseon adopted a tributary relationship with the Ming, sending annual diplomatic missions to the Ming Court, and Korea’s foreign policy, cultural and international economic ties became solely directed toward China as the country turned inward. Joseon King Sejong’s subsequent royal decree in 1427 to drive out foreign culture removed special status for the ‘Huihui,’ Korea’s Muslim community, prohibiting them from performing Islamic rites, wearing traditional dress or operating mosques. Joseon embraced a policy of isolation, which it maintained during the subsequent Qing Dynasty, earning Korea the name “Hermit Kingdom.” As in China, the ascendancy of traditional Neo-Confucianism reduced Buddhist influence, enhanced the social status of scholar-officials and reduced that of the merchant class.

Conclusion

While the flow of people, goods, and ideas along the Silk Roads to Korea has risen and fallen throughout history, the spread of political and religious ideologies has not always coincided with the movement of people or of goods. For instance, Yuan domination of Korea was characterized by the free movement of people and goods, without the widespread adoption of new political or religious ideas. Korea embraced its most radically new foreign political religious concepts from the Silk Road, namely the Shaman King and Buddhist Chakravartin King governing models, during the proto-Three Kingdom and Three Kingdoms period.

Different factors account for Korea’s openness to trade and amenability to new political and religious thought. Domination of trade connections to the Korea by free trading powers opened the peninsula to an inflow of goods and people. Prior to ascendancy of maritime trade this meant control of critical Northern Chinese Silk Road connections by free trading nomadic pastoral tribes and states, rather than sedentary agricultural civilizations. Thus, good moved freely along the Silk Road until nomadic pastoral groups lost influence with the rise of the Ming Dynasty. Heightened interstate competition in the Silk Road region of Northern China near Korea, but especially within the Korean peninsula, turned the interests of political elites in favor of adopting new political and religious ideologies to legitimate rule and maximize power, speeding the dissemination of new religious and political thought. Thus, the most radical adaptation of foreign religious and political thought occur in Korea during conditions of intense competition for survival between small states during the proto- Three Kingdoms and Three Kingdoms periods.

This two-factor model must be adjusted to take account of changing economic conditions. As technological shifts led maritime trade to replace overland exchange, domination of the Northern China Silk Road connections to Korea fell in importance. Merchant dominated states without any influence of nomadic pastoral herders, such as the Song Dynasty also adopted trade friendly policies. And more recently, industrialization and the rise of capitalism have led to the rise of free trade policies in countries throughout the world.

Still, this two-factor explanation for the flow of goods and political/religious thought can provide some insight into the likelihood of political change in North Korea. The Korean peninsula in the Cold War era was characterized by division into two states competing for political legitimacy, with trade connections to the South dominated by a free trading power (the U.S.) and connections to the North under the control of a state opposed to free trade (the Soviet Union). Thus, while South Korea embraced free trade, the North adopted autarky. Interstate competition led to the introduction of new ideologies to legitimate political authority, namely liberal democracy in the South and Marxism/Juche philosophy in the North. In the free trade South, which intentionally separated state from religion, a new faith (Christianity) gained followers throughout the country. While superficially adopting Marxism/Leninism, by invoking Juche philosophy the North in fact revived an ancient legitimating ideological strategy, creating a state religion asserting the ruling Kim family’s supernatural authority.

The collapse of the Soviet Union and its replacement as the North’s patron by free trading China opens up the potential flow of goods and ideas into the North. While the North’s legitimating ideology depends on blanket dissemination of state propaganda and thus has minimal impact outside the North, the South’s liberal democratic ideological values have broader appeal and have infiltrated commercial advertising and popular culture. By seeking to increase popularity through economic development and increased living standards the North’s Kim Jung Un has already adopted a strategy containing some liberal democratic elements– demonstrating a need to legitimate authority through accountability to the people rather than, or as a complement to, god-like powers. If history is a guide, conditions of interstate competition with the South will eventually force the North to adopt more liberal democratic reforms to maintain power, just as Silla’s competition with Baekje and Goguryeo led Silla’s Jinheung to adopt the Buddhist Chakravartin King model. One must also remember, though, that Silla required 150 years for this change.

References

“Buddhism Known in Emperor Qin's Time.”

China Daily. May 13, 2009. Accessed January 7, 2020. https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/life/2009-05/13/content_7772181.htm

Cambon, Pierre and Jean-François Jarrige.

Afghanistan – les Trésors Retrouvés [Afghanistan - Treasures Found]. Paris: Musée National des Arts Asiatiques-Guimet, 2006

.

Choe Byeong-hyeon.

Silla Gobun Yeongu 신라고분연구 [A Study on the Ancient Tombs of Silla]. Seoul Iljisa, 1992.

Deaton, Angus.

The Great Escape: Health, Wealth, and the Origins of Inequality. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2015.

Ekvall, Robert B. “The Nomadic Pattern of Living among the Tibetans as Preparation for War.”

American Anthropologist 63, (1961): 1250-1263. Accessed January 7, 2020. https://anthrosource.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1525/aa.1961.63.6.02a00060

Harrell, Mark. “Sokkuram: Buddhist Monument and Political Statement in Korea.”

World Archaeology 27, no. 2 (1995): 318-35.

Hildebrand, H. K.

Die Wildbeutergruppen Borneos [The Game Hunter Groups of Borneo]. Munich: Minerva, 1982.

Kim, Byung-mo.

Geumgwanui Bimil 금관의 비밀 [Secrets of the Golden Crowns]. Seoul: Korea Institute of Heritage, 1998.

Kim Han, Insung. “‘Look at the Alcohol If You Want to Know the Country’: Drinking Vessels as a Cultural Marker of Medieval Korea.”

Acta Via Serica 4, no. 2 (December 2019): 29-59.

Kwon, Young-pil. “West Asia and Ancient Korean Culture: Revisiting the Silk Road from an Art History Perspective.”

The International Journal of Korean Art and Archaeology 3, (March 2009): 152-169.

Kwon, Young-pil.

Silkeurodeu Misul: Jungang Asiaeseo Hangukkkaji 실크로드미술: 중앙 아시아에서한국까지 [Silk Road Art: From Central Asia to Korea]. Seoul: Yeolhwadang, 1997.

Lancaster, W. and F. Lancaster. “Desert Devices: The Pastoral System of the Rwalabedu.” In

The World of Pastoralism, edited by J. G. Galaty and D. L. Johnston. New York: Guilford, 1990.

Lee, Hee Soo. “Evaluation of Kushnama as a Historical Source in Regard to Descriptions of Basila.”

Acta Koreana 21, no. 1 (June 2018): 15–36.

Lee, Hee Soo. “The Socio-Economic Activities of Muslims and the Hui Hui Community of Korea in Medieval Times.”

Acta Via Serica 2, no. 1 (June 2017): 85-108.

Nelson, Sarah M.

Shamanism and the Origin of States: Spirit, Power, and Gender in East Asia. Walnut Creek, Calif.: Left Coast Press, 2008.

Rosen, Staffan. “Korea and the Silk Roads.”

The Silk Road 6, no. 2 (2009): 3-14.

Rudenko, Sergei Ivanovich.

Kul’tura Naseleniia Tsentral’nogo Altaia v Skifskoe Vremia [The Culture of the Population of the Central Altai in Scythian Times]. Leningrad: Izd-vo. AN SSSR, 1960.

The National Museum of Korea.

Hwanggeumui Jeguk Pereusia 황금의 제국 페르시아 [Persia the Golden Empire]. Seoul: The National Museum of Korea, 2008.

Weber, Max.

Basic Concepts in Sociology. New York: Citadel Press, 1962.

Yi, Song-nan.

Hwangnam Daechong Sillagwanui Gisuljeok Gyebo 황남 대총 신라관의 기술적 계보 [A Technical Lineage of the Silla Crowns from the Hwangnam Grand Tomb]. Seoul: Nurimedia, 2005.

1 See H. K Hildebrand,

Die Wildbeutergruppen Borneos [The Game Hunter Groups of Borneo] (Munich: Minerva, 1982); W. Lancaster and F. Lancaster, “Desert Devices: The Pastoral System of the Rwalabedu,” in

The World of Pastoralism, eds. J. G. Galaty and D. L. Johnston (New York: Guilford, 1990).

2See Max Weber,

Basic Concepts in Sociology (New York: Citadel Press, 1962).

3See Robert B. Ekvall, “The Nomadic Pattern of Living among the Tibetans as Preparation for War,”

American Anthropologist 63, (1961): 1250-1263. Accessed January 7, 2020. https://anthrosource.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1525/aa.1961.63.6.02a00060.

4See Sarah M. Nelson,

Shamanism and the Origin of States: Spirit, Power, and Gender in East Asia (Walnut Creek, Calif.: Left Coast Press, 2008).

5See Byeong-hyeon Choe,

Silla Gobun Yeongu 신라고분연구[A Study on the Ancient Tombs of Silla] (Seoul Iljisa, 1992); Byung-mo Kim, Geumgwanui Bimil 금관의 비밀 [Secrets of the Golden Crowns] (Seoul: Korea Institute of Heritage, 1998).

6See Song-nan Yi,

Hwangnam Daechong Sillagwanui Gisuljeok Gyebo 황남 대총 신라관의 기술적 계보 [A Technical Lineage of the Silla Crowns from the Hwangnam Grand Tomb] (Seoul: Nurimedia, 2005).

7See Pierre Cambon and Jean-François Jarrige, Afghanistan –

les Trésors Retrouvés [Afghanistan - Treasures Found] (Paris: Musée National des Arts Asiatiques-Guimet, 2006).

8Cambon, Afghanistan –

les Trésors Retrouvés.

9Yi,

Hwangnam Daechong Sillagwanui Gisuljeok Gyebo.

10See Sergei Ivanovich Rudenko,

Kul’tura Naseleniia Tsentral’nogo Altaia v Skifskoe Vremia [The Culture of the Population of the Central Altai in Scythian Times] (Leningrad: Izd-vo. AN SSSR, 1960).

11See Byung-mo Kim,

Geumgwanui Bimil 금관의 비밀 [Secrets of the Golden Crowns] (Seoul: Korea Institute of Heritage, 1998).

12See Staffan Rosen, “Korea and the Silk Roads,”

The Silk Road 6, no. 2 (2009): 3-14.

13See Young-pil Kwon, “West Asia and Ancient Korean Culture: Revisiting the Silk Road from an Art History Perspective,”

The International Journal of Korean Art and Archaeology 3, (March 2009): 152-169.

14Archeologist Han Wei claims that the Qin Emperor, Qin Shi Hwang banned Buddhism See “Buddhism known in Emperor Qin's Time,”

China Daily, May 13, 2009, Accessed January 7, 2020. https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/life/2009-05/13/content_7772181.htm.

15The Rebellion of Hou Jin (548), near the end of Emperor Wu's reign, destroyed the political privileges of the elite clans, assisting Buddhism’s spread throughout southern China.

16Harrell argues that Seokguram provides a model of the ideal political state. The Buddha, who expounds his teachings, is shown served by his bodhisattva intermediaries and attended to by a large community of monks. The Silla King is served by his political advisers and court and loyally followed by the nation. A worshipper at Seokguram pays respects to both systems, which serve one another. Seokguram overlooks the underwater mausoleum of King Munmu the Great who unified the Korean peninsula under Silla Rule. See Mark Harrell, “Sokkuram: Buddhist Monument and Political Statement in Korea,”

World Archaeology 27, no. 2 (1995): 318-35.

17See The National Museum of Korea,

Hwanggeumui Jeguk Pereusia 황금의 제국 페르시아 [Persia the Golden Empire]. Seoul: The National Museum of Korea, 2008.

18See Young-pil Kwon, Silkeurodeu Misul: Jungang Asiaeseo Hangukkkaji 실크로드미술: 중앙 아시아에서한국까지 [Silk Road Art: From Central Asia to Korea] (Seoul: Yeolhwadang, 1997).

19Kwon,

Silkeurodeu Misul: Jungang Asiaeseo Hangukkkaji.

20The Tang also enforced strict border laws, with many government checkpoints to examine travel permits along the Silk Road, however.

21A 2014 book

Kushnameh in Korea, claims that a Sassanid prince named Abtin immigrated with his subjects to Silla, where he married a Silla princess named Frarang. See Hee Soo Lee, “Evaluation of Kushnama as a Historical Source in Regard to Descriptions of Basila,” Acta Koreana 21, no. 1 (June 2018): 15–36.

22Goryeosa (The Official Chronicles of the Goryeo Dynasty) records a large scale caravan of around 100 Arab and Persian merchants in 1024 and 1025, while the fourteenth-century historian Rashid al-Din of the Mongol Ilkhanate described Goryeo in his book Jami’ al-tawarikh. See Lee, “Evaluation of Kushnama as a Historical Source in Regard to Descriptions of Basila,” 6.

23Goryeo’s celadon pottery is considered by experts to be made with some of the most advanced technology and craftsmanship in with world, with delicate shapes, varied colors, and intricate designs.

24Some instances of Central Asian immigrants include Samga, the Uighur progenitor of the Deoksu Jang clan and Seol Son, the progenitor of the Gyeongju Seol clan. See Hee Soo Lee, “The Socio-Economic Activities of Muslims and the Hui Hui Community of Korea in Medieval Times,”

Acta Via Serica 2, no. 1 (June 2017): 85-108.

25See Lee, “Evaluation of Kushnama as a Historical Source in Regard to Descriptions of Basila.” 15–36.

26See Insung Kim Han, “‘Look at the Alcohol If You Want to Know the Country’: Drinking Vessels as a Cultural Marker of Medieval Korea,”

Acta Via Serica 4, no. 2 (December 2019): 29-59.

27These incude Suryeopdo (Hunting Scene) and Gima dogangdo (Horse Riders Crossing a River) by Yi Jehyeon. See Kwon, Silkeurodeu Misul: Jungang Asiaeseo Hangukkkaji.

28See Angus Deaton,

The Great Escape: Health, Wealth, and the Origins of Inequality (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2015).

This article was funded by the Project of Silk Road Humanities 2019,

sponsored by Gyeongsangbuk-do Province

Copyright© Academia Via Serica. All Right Reserved.